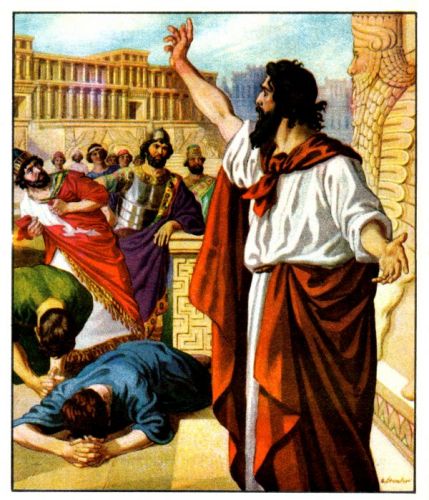

Your recent entries to the site "Jonah the Prophet" [see previous post] have prompted this comment from me.

I too have noticed striking similarities of textual matter and style between the Scriptural stories of Noah and Jonah, and have done a bit of research in this area. You may like to refer to the Concordia Seminary of St. Louis website ( <http://seminary.csl.edu/facultypubs/TheologyandPractice/tabid/87/ctl/Details/mid/494/ItemID/40/Default.aspx> ) where the following is noted;

“Another example demonstrating that the narrator of Jonah employs earlier texts – while also subtly changing them – is his use of the Noah cycle. In a broader stroke Eric Hesse and Isaac Kikawada believe that there are numerous connections between Jonah and Genesis 1-11, but what follows is a representative list of phrases, characters, and images from Genesis 5:28 10:32 that find resonance within the narrative of Jonah. First, “one hundred twenty years” (Gen 6:3) – this is the length of time allotted by Yahweh to human life; it is also how many thousands of people are in Nineveh at the narrative’s end (4:11). Second, “the evil of humankind” (Gen 6:5) – this is what Yahweh observes on the face of the earth; it is also what has come to his attention with respect to the Ninevites in Jonah 1:2 (“for their evil has come up before me”). Third, Yahweh changes his mind (Gen 6:6) concerning his very good creation (Gen. 1:31) and wants to destroy it. Yahweh’s change of mind is what the Ninevites bank on in Jonah 3:9 (“who knows, God may turn and change his mind …”). This is exactly what God does in 3:10; in 4:2 Jonah states that it is Yahweh’s nature to do this. The fourth connection between Noah and Jonah is the phrase “... people together with animals” (Gen 6:7). This phrase – or something very similar to it – occurs throughout the Noah narrative (e.g. Gen. 7:23); the book of Jonah is remarkable for its very deliberate inclusion of animals along with people, both in how the Ninevites and their animals repent (3:7-9) and in how God presents his final question to Jonah (4:10-11). Fifth, violence (Gen 6:11) is the reason given for God's decision to destroy the earth and its inhabitants by means of the Flood; it is also the sin that the Ninevites recognize as their own, and repent of (3:8). Sixth, “forty days and forty nights” (Gen 7:4) is the period of time that the rains last, destroying all human and animal life that is not with Noah in the ark. Similarly, this is the amount of time from the moment of Jonah's prophecy until Nineveh is to be “turned upside down” (3:4). This association of “forty days” as a period of testing with the result of a new beginning is a link to these two stories. The seventh connection is the phrase “and God made a wind blow” (Gen 8:1). Through the Flood narrative Yahweh actively controls individual winds for specific purposes; for example in Gen. 8:1 he manages the wind to cause the flood waters to subside. In Jonah, Yahweh hurls a wind into the sea to create a storm (1:4) and, later, sends a searing wind from the east that adds to Jonah's misery (4:8). Eighth, the statement “… nor will I ever again destroy every living creature as I have done" (Gen 8:21) is the eternal pledge that Yahweh makes to Noah, his family, and to all living creatures after the Flood. This pledge is, to a great extent, the motivation behind Jonah's refusal to be Yahweh’s prophet to Nineveh as he knows that this God has voluntarily given up total destruction (at least by Flood) as a means for dealing with the habitually violent (4:2). The final example of intertextual echoes from Noah to Jonah is Yahweh’s promise, “I am establishing my covenant with you and your descendants after you, and with every living creature ... my covenant that is between me and you and every living creature of all flesh” (Gen. 9:9a, 10a). In this covenant Yahweh specifically includes not only humankind but also animals, domestic and wild. This means that the umbrella of this covenant is extended to non Israelite humans (the Ninevites) as well as their animals, whose donning of sackcloth and bleating perhaps serve to remind Yahweh of this promise (3:7-9).” There is more, but you get the idea (I would urge anyone interested in this area of research to visit the Concordia website and read the entire article where there are some intriguing connections between Elijah and Jonah as well).

I have been using this line of reasoning to explain certain obvious references to the story of Noah in the Greek myth of Jason (possibly a shibboleth of the Greek version of the name of Jonah, “Jonas”) and the Argonauts (It must furthermore be admitted that there are also several references to the story of Eden, Abraham, and the Exodus in the tale.). Such Noahic references include the release of a dove by the captain of the Argo in order to determine whether it is safe to proceed (the dove also figures in the story of Jonah in that the name “Jonah” means “dove.”). Also the name of the ship itself “the Argo” is plausibly somehow related to the “name” of Noah’s ship the Ark. Jason’s Argonauts are often represented to as “Minyans” and the story “Argonautica” is called by the Greek mythographers “the Minyan tale.” The "Minni," named in connection with Ararat, by Jeremiah (from Jeremiah 51:27), are the same People as those mentioned by Josephus (quoting Nicolaus of Damascus), who uses the Greek form "Minyas," (Antiquities i. I. 6,) to indicate a place in Armenia, the country where Noah’s Ark landed (The idea being that the Minyans, connected with the Argonautica, certainly would have been aware of the story of Noah‘s Ark.). In fact, the general destination of the Agro, Colchis, could easily be considered as a subdivision of the land of Ararat (Urartu) where the Ark landed. Lastly there is the main theme of the Book of Jonah, namely that the God of Jonah is the God, not only of the Israelites but of the whole world. Similarly the occupants of the Ark are the ancestors of all of mankind and the religion and laws that were propagated by Noah are universally applicable. The Jewish Legends by Ginzberg relate the notion that the companion sailors of Jonah were representatives from every nation on Earth and the “cargo” that they carried (and jettisoned to lighten the load) was actually each one’s particular idol. Likewise the companions of Jason were the “heroes” from each of the city-states of Greece and the purpose of the tale was to join them all in the same religious quest.

-John R. Salverda