Historical Window for Jonah’s Nineveh Visit

Part Five (i): Did Jonah’s visit inspire monotheism in the kingdom of Assyria?

by

Damien F. Mackey

“A strange religious revolution took place in the time of Adad-nirari III, which can be compared with that of the Egyptian Pharaoh Ikhnaton. For an unknown reason Nabu (Nebo), the god of Borsippa, seems to have been proclaimed sole god, or at least the principal god, of the empire”.

Francis D. Nichol

Introduction

Whilst I would once have thought that Akhnaton’s Atonism influencing the ‘Nebo revolution’ was likely – then having king Adad-nirari III following on closely from the El Amarna [EA] age (revised) – I would now, with my lowering of this neo-Assyrian period by up to a century:

Re-shuffling the Pack of Neo-Assyrian Kings

and with the prophet Jonah and his mission now located to the very eve of the reign of a revised Adad-nirari III (perhaps when a high official such as Ahikar was “king [governor] of Nineveh):

Book of Jonah’s ‘King of Nineveh’

consider the “strange religious revolution” of pharaoh Akhnaton and Queen Nefertiti to be entirely a different one (chronologically and theologically) from that thought to have occurred at the time of neo-Assyrian king Adad-nirari III.

On a previous occasion I had written: My reconstruction of EA (Akhnaton and Nefertiti) in its relation to the time of Ahab and Jezebel has led me to conclude that the Baalism that the Bible records at this time was reflected in the Atonism of, principally, Akhetaton in Egypt, and that the erasure of that Baalism was done through the same agency that defaced and erased Akhnaton and his unique project. Now I learn from Mackenzie’s article (Donald A. MacKenzie, Myths of Babylonia and Assyria, 1915) that a similar régime as Akhnaton’s was effected in Assyro-Babylonia at the time of Adad-nirari III (or IV: Mackenzie), with the legendary Queen Sammuramat (or Semiramis) having unique power for a woman, likened (once more, as in the case of the Jezebel seal) to Queen Tiy. My conclusion will be that Sammuramat was Nefertiti/Tiy (Jezebel) in Mesopotamia. [End of quote] Whilst I still firmly hold Queen Nefertiti to have been the biblical bad-woman, Jezebel:

Queen Nefertiti Sealed as Jezebel

https://www.academia.edu/31088456/Queen_Nefertiti_Sealed_as_Jezebel I would now no longer extend this alter ego-ism to include Queen Tiy. And Queen Sammuramat (‘Semiramis’), for her part, can no longer belong to the EA era according to my more recent revision of her – now equating her with the significant neo-Assyrian queen, Naqia (Zakutu):

The influence of the two historical queens, Nefertiti and Naqia, ought not to be underestimated. If Nefertiti were Jezebel, as I maintain, then she was one who actually spurred on her husband, and may therefore have been instrumental in fostering the strange and somewhat Indic cult of Atonism in EA’s Egypt. The very first we hear of Jezebel is in association with Baal worship (I Kings 16:31): “[King Ahab] also married Jezebel daughter of Ethbaal king of the Sidonians, and began to serve Baal and worship him”. And she, again, was apparently the wind beneath his idolatrous wings (I Kings 21:25): “… there was no one like Ahab who sold himself to do wickedness in the sight of the LORD, because Jezebel his wife stirred him up”.Likewise, Queen Semiramis may have been instrumental in the case of the (different) religious reform at the time of Adad-nirari III. Writing of “The Age of Semiramis” in his Chapter XVIII, Donald MacKenzie will make some interesting observations about her, including this one: “Queen Sammu-rammat of Assyria, like Tiy of Egypt, is associated with social and religious innovations”. Here is a part of MacKenzie’s intriguing account of this semi-legendary queen:

…. One of the most interesting figures in Mesopotamian history came into prominence during the Assyrian Middle [sic] Empire period. This was the famous Sammu-rammat, the Babylonian wife of an Assyrian ruler. Like Sargon of Akkad, Alexander the Great, and Dietrich von Bern, she made, by reason of her achievements and influence, a deep impression on the popular imagination, and as these monarchs became identified in tradition with gods of war and fertility, she had attached to her memory the myths associated with the mother goddess of love and battle who presided over the destinies of mankind. In her character as the legendary Semiramis of Greek literature, the Assyrian queen was reputed to have been the daughter of Derceto, the dove and fish goddess of Askalon, and to have departed from earth in bird form.

It is not quite certain whether Sammu-rammat was the wife of Shamshi-Adad VII [we now take this as V] or of his son, Adad-nirari IV [III]. Before the former monarch reduced Babylonia to the status of an Assyrian province, he had signed a treaty of peace with its king, and it is suggested that it was confirmed by a matrimonial alliance. This treaty was repudiated by King Bau-akh-iddina, who was transported with his palace treasures to Assyria.

As Sammu-rammat was evidently a royal princess of Babylonia, it seems probable that her marriage was arranged with purpose to legitimatize the succession of the Assyrian overlords to the Babylonian throne. The principle of “mother right” was ever popular in those countries where the worship of the Great Mother was perpetuated if not in official at any rate in domestic religion. Not a few Egyptian Pharaohs reigned as husbands or as sons of royal ladies. Succession by the female line was also observed among the Hittites. When Hattusil II gave his daughter in marriage to Putakhi, king of the Amorites, he inserted a clause in the treaty of alliance “to the effect that the sovereignty over the Amorite should belong to the son and descendants of his daughter for evermore”.[464]

As queen or queen-mother, Sammu-rammat occupied as prominent a position in Assyria as did Queen Tiy of Egypt during the lifetime of her husband, Amenhotep III, and the early part of the reign of her son, Amenhotep IV (Akhenaton). The Tell-el-Amarna letters testify to Tiy’s influence in the Egyptian “Foreign Office”, and we know that at home she was joint ruler with her husband and took part with him in public ceremonials. During their reign a temple was erected to the mother goddess Mut, and beside it was formed a great lake on which sailed the “barque of Aton” in connection with mysterious religious ceremonials. After Akhenaton’s religious revolt was inaugurated, the worship of Mut was discontinued and Tiy went into retirement. In Akhenaton’s time the vulture symbol of the goddess Mut did not appear above the sculptured figures of royalty.

What connection the god Aton had with Mut during the period of the Tiy regime remains obscure. There is no evidence that Aton was first exalted as the son of the Great Mother goddess, although this is not improbable.

Queen Sammu-rammat of Assyria, like Tiy of Egypt, is associated with social and religious innovations. She was the first, and, indeed, the only Assyrian royal lady, to be referred to on equal terms with her royal husband in official inscriptions. In a dedication to the god Nebo, that deity is reputed to be the protector of “the life of Adad-nirari, king of the land of Ashur, his lord, and the life of Sammu-rammat, she of the palace, his lady”.[465]

During the reign of Adad-nirari IV the Assyrian Court radiated Babylonian culture and traditions. The king not only recorded his descent from the first Shalmaneser, but also claimed to be a descendant of Bel-kap-kapu, an earlier, but, to us, unknown, Babylonian monarch than “Sulili”, i.e. Sumu-la-ilu, the great-great-grandfather of Hammurabi. Bel-kap-kapu was reputed to have been an overlord of Assyria.

Apparently Adad-nirari desired to be regarded as the legitimate heir to the thrones of Assyria and Babylonia. His claim upon the latter country must have had a substantial basis. It is not too much to assume that he was a son of a princess of its ancient royal family. Sammurammat may therefore have been his mother. She could have been called his “wife” in the mythological sense, the king having become “husband of his mother”. If such was the case, the royal pair probably posed as the high priest and high priestess of the ancient goddess cult–the incarnations of the Great Mother and the son who displaced his sire.

The worship of the Great Mother was the popular religion of the indigenous peoples of western Asia, including parts of Asia Minor, Egypt, and southern and western Europe. It appears to have been closely associated with agricultural rites practised among representative communities of the Mediterranean race. In Babylonia and Assyria the peoples of the goddess cult fused with the peoples of the god cult, but the prominence maintained by Ishtar, who absorbed many of the old mother deities, testifies to the persistence of immemorial habits of thought and antique religious ceremonials among the descendants of the earliest settlers in the Tigro-Euphrates valley. ….

It must be recognized, in this connection, that an official religion was not always a full reflection of popular beliefs. In all the great civilizations of antiquity it was invariably a compromise between the beliefs of the military aristocracy and the masses of mingled peoples over whom they held sway. Temple worship had therefore a political aspect; it was intended, among other things, to strengthen the position of the ruling classes. But ancient deities could still be worshipped, and were worshipped, in homes and fields, in groves and on mountain tops, as the case might be. Jeremiah has testified to the persistence of the folk practices in connection with the worship of the mother goddess among the inhabitants of Palestine. Sacrificial fires were lit and cakes were baked and offered to the “Queen of Heaven” in the streets of Jerusalem and other cities. In Babylonia and Egypt domestic religious practices were never completely supplanted by temple ceremonies in which rulers took a prominent part. It was always possible, therefore, for usurpers to make popular appeal by reviving ancient and persistent forms of worship. As we have seen, Jehu of Israel, after stamping out Phoenician Baal worship, secured a strong following by giving official recognition to the cult of the golden calf.

MacKenzie now proceeds to draw his hopeful religious parallel between EA and Sammuramat alongside Adad-nirari III:

It is not possible to set forth in detail, or with intimate knowledge, the various innovations which Sammu-rammat introduced, or with which she was credited, during the reigns of Adad-nirari IV (810-782 B.C.) and his father. No discovery has been made of documents like the Tell-el-Amarna “letters”, which would shed light on the social and political life of this interesting period.

…. The prominence given to Nebo, the god of Borsippa, during the reign of Adad-nirari IV is highly significant. He appears in his later character as a god of culture and wisdom, the patron of scribes and artists, and the wise counsellor of the deities. He symbolized the intellectual life of the southern kingdom, which was more closely associated with religious ethics than that of war-loving Assyria.

A great temple was erected to Nebo at Kalkhi, and four statues of him were placed within it, two of which are now in the British Museum. On one of these was cut the inscription, from which we have quoted, lauding the exalted and wise deity and invoking him to protect Adad-nirari and the lady of the palace, Sammu-rammat, and closing with the exhortation, “Whoso cometh in after time, let him trust in Nebo and trust in no other god”.

In light of my revisions, however, I would be more likely to conclude now with the view expressed in the following piece, conventionally dated, that this apparent unexpected reversion of Assyria to a religious form of monotheism was due to the effects of “Jonah’s mission to Nineveh” (http://bibarchae.tripod.com/001_Attendant_god_Nabu_Nimrud.htm):

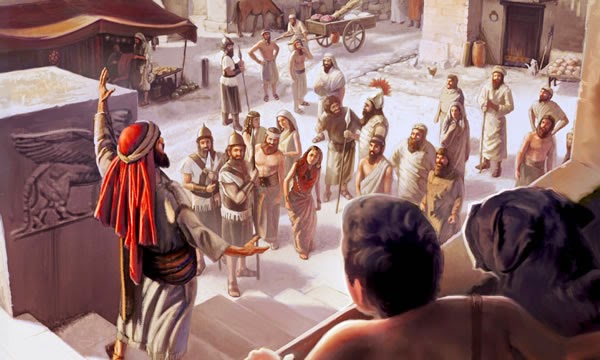

Attendant god, 810 – 800 BC, Temple of Nabu, Nimrud (Kalhu) [see above]

This is one of a pair of statues that stood outside the doorway of the temple of Nabu, god of writing. The cuneiform inscription on it (translation available here) mentions King Adad-Nirari III (810-783 BC), and his powerful mother, queen Sammuramat (Semiramis). The end of the inscription says, “Trust in Nabu, do not trust in any other god”. Clasping the hands together over or just below the chest, with the right hand over the left, whilst in a standing position, is very common posture in mesopotamian statues, and I think it is a votive gesture done by worshippers. It is still done today, as part of the Muslim prayer ritual.

This is one of a pair of statues that stood outside the doorway of the temple of Nabu, god of writing. The cuneiform inscription on it (translation available here) mentions King Adad-Nirari III (810-783 BC), and his powerful mother, queen Sammuramat (Semiramis). The end of the inscription says, “Trust in Nabu, do not trust in any other god”. Clasping the hands together over or just below the chest, with the right hand over the left, whilst in a standing position, is very common posture in mesopotamian statues, and I think it is a votive gesture done by worshippers. It is still done today, as part of the Muslim prayer ritual.

This is the first photo I took. The statue is the first thing you see on the right of room 6, the start of the Ancient Near East section on the ground floor of the west wing of the museum. Below is an excerpt from the SDA Bible Commentary that is related to it. It says that the statue is of Nabu, set up by a governor dedicated to the king, but the museum sign said it was of an attendant god and dates it older than in the article below:

“A strange religious revolution took place in the time of Adad-nirari III, which can be compared with that of the Egyptian Pharaoh Ikhnaton. For an unknown reason Nabu (Nebo), the god of Borsippa, seems to have been proclaimed sole god, or at least the principal god, of the empire. A Nabu temple was erected in 787 B.C. at Calah, and on a Nabu statue one of the governors dedicated to the king appear the significant words, “Trust in Nabu, do not trust in any other god” The favorite place accorded Nabu in the religious life of Assyria is revealed by the fact that no other god appears so often in personal names. This monotheistic revolution had as short a life as the Aton revolution in Egypt. The worshipers of the Assyrian national deities quickly recovered from their impotence, reoccupied their privileged places, and suppressed Nabu. This is the reason that so little is known concerning the events during the time of the monotheistic revolution. Biblical chronology places Jonah’s ministry in the time of Jeroboam II, of Israel, who reigned from 793 to 753 b.c. Hence, Jonah’s mission to Nineveh may have occurred in the reign of Adad-nirari III, and may have had something to do with his decision to abandon the old gods and serve only one deity. This explanation can, however, be given only as a possibility, because source material for that period is so scanty and fragmentary that a complete reconstruction of the political and religious history of Assyria during the time under consideration is not yet possible”.

[End of quote]

With Adad-nirari III greatly filled out as Esarhaddon, however, as according to my revisions, then the “scanty and fragmentary” “source material for that period” correspondingly gets filled out. The Assyrian inscription reading “… trust in Nebo and trust in no other god” is purely Yahwistic and Isaianic (26:4): “Trust in the LORD forever, for the LORD, the LORD himself, is the Rock eternal”. Nor is it surprising to find there an echo of the contemporaneous Isaiah, given that (https://www.studylight.org/commentaries/bcc/jonah-3.html)

Jeremiah and Isaiah both were doubtless influenced by Jonah, especially Isaiah who, in full harmony with the inevitable deductions that appear mandatory in the Book of Jonah, prophesied again and again the rejection of Israel and the acceptance of the Gentiles into the kingdom of God.